Labor Day means no more wearing seersucker

Wait, what the hell is seersucker?

On May 24, 1890, eccentric wealth-monster George Francis Train returned from a 67-day trip around the world, undertaken just to better journalist Nellie Bly’s famous 72-day trip from a few months earlier. All along the way, he wore his trusty, summery seersucker suit. “Universe laughed at my seersucker suit,” he told the New Orleans Picayune. “Now I laugh at universe. I am the seer. Universe is the sucker.”

But long before Gilded Age weirdos were going to an awful lot of trouble to randomly one-up intrepid women, seersucker was already well-known in other parts of the world. The word comes from the Persian phrase “shir-o-shakhar” — “milk and sugar” — because of the different textures of its side-by-side stripes (originally cotton and silk; now just different textures of cotton). Vocabulary.com explains that the East India Company started exporting the fabric in the late 1600s; a poster dating back to 1694 detailed cargo that had just arrived in London, which included damask, gingham, and seersucker fabric.

By the early 18th century, seersucker had landed in America, where it became an increasingly popular choice during Southern summers. (Anyone who’s sweated through a Carolina August knows what a difference the right clothing can make). But, perhaps more than any other city, it was in New Orleans that seersucker became the hottest… er, coolest thing going.

Lydia Blackmore, the Curator of Decorative Arts at the Historic New Orleans Collection, said that the city’s earliest reference was an 1867 newspaper ad for the excellently named Robert Pitkins’ Fashionable Clothing Emporium. Thirty years later – not too long after George Francis Train’s mash note – the Godchaux Department Store was advertising them for $12 each (about $440 today), and Mayer Israel & Co. said their seersucker suits were “made to measure” in their 1906 summer ads.

Throughout the 20th century, bolstered by Southern summering for East Coast elites, and by a collegiate fad that spread out from the Ivy League, seersucker got an increasingly preppy reputation. This perception was hypercharged in the late 1990s, when former senator Trent Lott (R-Miss.) – otherwise remembered for casually endorsing a segregationist and for being tricked by one of Sacha Baron Cohen’s least-believable characters –- brought “Seersucker Thursday” to Capitol Hill.

According to the Senate historian, Lott pitched a “nice and warm day” in June as the day for senators to wear their best (or only) seersucker suits to work, so they could “lighten up and loosen up.” In 2005, Dianne Feinstein (D-Ca.) gifted some seersucker ensembles to her female colleagues, so they could look stylishly rumpled too.

But perhaps no one is more synonymous with seersucker than New Orleans clothier Joseph Haspel Sr. who, according to the Haspel website, “was the first to recognize the power of the pucker.” Though his claim that he invented the seersucker suit in 1909 is slightly dubious — just re-read literally all of the above — he did help to popularize the style, convincing businessmen that his suits were what they needed to be slightly less miserable during those pre-air conditioned summers. Haspel still flogs the suits to this day, with full stretch tuxedos starting at $750.

“We’re the originators,” CEO and Haspel family scion Laurie Aronson told CNN in 2013. “Not the imitators.”

Not exactly George Francis Train catchy, but it’ll do.

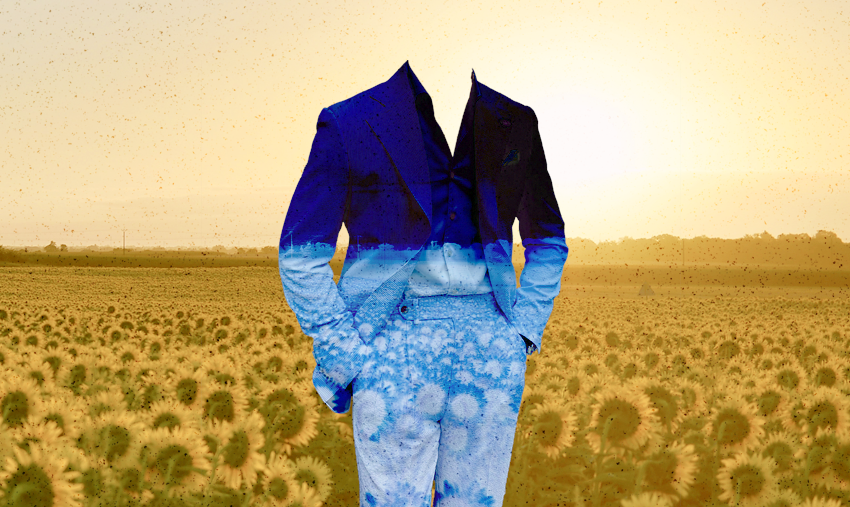

Photo illustration: Peter de Vink (Pexels) / Public Domain (rawpixel) / Questionist